PART 3

BUDGETS & CONTRACTS

Budgets

When working on shoestring budget films, it’s been my experience that budget is the one place where there is very little, of often no wiggle room for negotiation. They have what they have, take it or leave it. As I discussed earlier in Reasons for taking a shoestring budget project, money is rarely one of the reasons to agree to do it. Make sure there are enough reasons to say yes regardless of the budget. Again your reasons can change over time depending on your circumstance and where you are in your career, but whatever the case, make sure your’e comfortable with the decision to say yes.

Consider how much you need to pay yourself (if anything) and the rest of the money is your production budget. This is money you can use towards hiring musicians, getting help, buying gear, or new sample libraries, or plug-ins, whatever you may need.

Next identify your creative priorities, that’s what should dictate where you should spend whatever budget you have. You’re going to be wearing a lot of hats and doing a lot (if not everything) on your own. But consider your strengths and weaknesses, and your weaknesses are likely another place where you will spend your budget. Once you’ve identified where you want to spend your money, create a detailed budget so that you have a plan and stick to it.

At times after beginning work, you may discover that you want to spend money on something unanticipated, or perhaps certain costs are higher than expected. These may be opportunities to discuss coming up with more money with your filmmakers, or if you don’t think there’s any room for discussion you need to decided whether you’ll absorb that added cost or figure out another way to get the job done without the added cost.

For example, when I scored Lost Time, the director & I discussed that I would be creating a MIDI score. However at some point we realized we wanted to add a solo violin and solo cello, and while my programming and samples were pretty good, we both felt it wasn’t quite as good as we wanted. I called a couple of friends and got cost estimate from them, and then I reached out to the director and explained how much it would cost. We ended up splitting the cost, he came up with half the money, and I paid for the rest out of my initial fee. We were both thrilled with the result and he felt it was well worth the extra cost, and I was happy not to have to absorb the entire cost on my own. Win win.

When recording live musicians there are lots of options these days. As I mentioned earlier, if you can do it yourself, great, that’s the most cost-effective solution. But if not and you need to hire individual musicians to record remotely, plan on paying about $100 an hour for most good players (assuming non-union recording).

When recording an orchestra you also have lots of options. You can record under AFM contract in Los Angeles. This will usually be the most expensive way to go, and you’d need your project to become a signatory with all the strings that are attached. But in return you’ll get some of the best players on the planet, you’ll be supporting your local community of musicians, you’ll be working at great studios and you’ll have the convenience of being local. Depending on where you record & which musicians you use, there’s also a “cool factor” that can’t quite be quantified.

Years ago I recorded a demo under AFM contract. I remember for one particular cue, although the music was quite different, I wanted my snare to sound like the snare in the beginning of James Horner’s score to Glory. I was talking to my percussionist Bob Zimmitti about it and to my surprise and elation his response was (I’m paraphrasing) “I played on that score, I’ll bring that same snare drum.” How incredibly cool is that? And if you’re curious, here’s the cue

But recording under AFM contract isn’t the only way to go. There are so many orchestras around the world that are available and can be a good fit for your needs, usually at a much lower cost and at a buyout, meaning you don’t have to deal with residuals like on an AFM contract. You can find orchestras in Seattle, Nashville, London, Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, Macedonia and on and on. Each has their strengths and weaknesses.

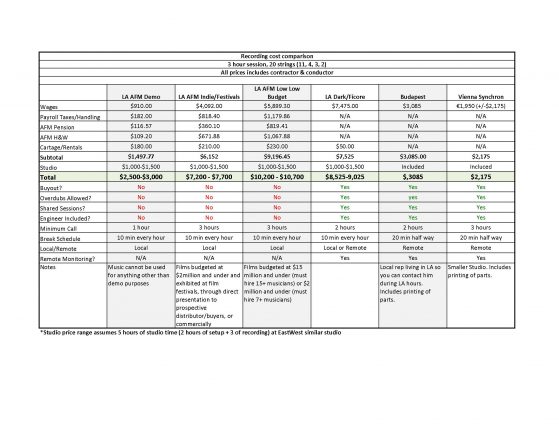

The biggest upside to recording with a non-union orchestra, especially oversees in Europe, is that it is a buyout recording, meaning you own the recording outright with no strings attached, and they are significantly cheaper than recording in LA, especially under AFM contract. The downsides are that many of these orchestras aren’t quite as good as our incredible local musicians; some of the studio facilities aren’t as great as our local facilities; and you’re working remotely which means going slower than when you’re in the same room, not to mention often working very early in the morning or overnight due to time-zone differences. You’ll also likely spend more time editing the recordings from these sessions than you would recordings done here in town. All that said, here is chart comparing the cost of recording 20 strings using different scenarios local and foreign. This should give you some idea of the differences in cost and services available.

In addition to the musician costs, you need to consider your studio choice (if recording locally, usually when recording overseas there isn’t a choice). First consider if you really need to get into a studio, or can you record what you need at home or with some individual remote sessions? If you do need a studio to record a group, consider what’s appropriate for your needs. For example, going to the Newman scoring stage at FOX to record a soloist wouldn’t be very practical, especially on a shoestring budget. However if you’re trying to impress your client and can afford it, paying a little extra for Capitol studio B vs. another comparable studio may be worth the added cost. Conversely if you’re just trying to get the job done as cost effectively as possible, use every connection you have to find cheap solutions.

For example, early in my career when I worked at a production facility, I had access to the studios late at night and I would bring in musicians to record my own stuff after hours. If your’e a composer’s assistant and your boss has a recording space, ask if you may use it on your own time. When I needed to record the vocals for the opening and end credit song for Captain Hagen’s Bed & Breakfast, I asked my good friend John Swihart if I could use his studio and he was kind enough to allow me to do so. It cost me nothing (I think I paid for lunch the next time we got together).